Drawing on his extensive insight and all the data he can lay his hands on, Professor Chris Elliott reveals the areas most at risk of exploitation in our food system, highlighting the questionable benevolence of AI as both friend and foe.

Food fraud has never been a static form of crime; it changes due to many factors but as we enter 2026 I believe its evolution is accelerating.

The challenge for regulators and industry the world over is no longer to merely identify where food fraud exists or acknowledge the growing role of organised crime; both are now given. The hard part is attempting to determine where it will do the greatest damage next. ”

What we are now witnessing is not just more fraud, but also different forms of fraud shaped by climate disruption, geopolitical tension, regulatory change, digital trade, sustained price volatilities and artificial intelligence (AI).

The challenge for regulators and industry the world over is no longer to merely identify where food fraud exists or acknowledge the growing role of organised crime; both are now given. The hard part is attempting to determine where it will do the greatest damage next. I have looked at multiple evidence sources ranging from confidential conversations, enforcement intelligence, regulatory alerts, academic literature, trade flows and media reports, along with some AI modelling tools, to help identify some key food commodities and ingredients that should be viewed as ‘high risk’ for 2026 and beyond. I’ve also attempted, for the first time I believe, to seriously consider how AI may be used as an enabler for new forms of fraud and to upscale existing threats.

Some may think my ‘risk lists’ are purely speculative, but they are based on all the data I could possibly access. I have also paid particular attention to how sustainability, in terms of consumer demands and regulations – most notably the EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR), is likely to impact the future food fraud landscape. The following are my four risk lists:

List 1: the ‘known knowns’

These are high-value and globally traded products. Olive oil, honey, seafood, spices, dairy, cocoa, coffee, nuts and alcohol repeatedly emerge as priority risks as they have done for some time. The likelihood that they will not only remain as targets for fraudsters but will increase in scale is largely driven by climate change and disease-linked crop failures, as well as shortages of or indeed excess water. They are also commodities that invite fraud due to long and complex supply chains.

List 2: the ‘EUDR list’

The five core food-related commodities – beef, cocoa, coffee, palm oil and soya – are highly likely to experience new and more sophisticated forms of fraud from 2026, facilitated by large-scale data and provenance manipulation.

For cattle and beef, fraud will likely centre on falsified geolocation data, falsified farm identities and cattle laundering. Cocoa and coffee (notably also in List 1), particularly from West Africa and Latin America, will be vulnerable to falsified deforestation-free histories, cooperative-level document laundering and blending of non-compliant production into compliant export streams. Palm oil fraud is likely to involve companies setting up complex business structures, redrawing or misreporting plantation boundaries and altering maps or records to hide recent deforestation or land-use changes. For soya, especially from Brazil, fraud will likely exploit aggregation points such as silos and traders, where compliant and non-compliant harvests can be mixed while maintaining apparently trustworthy paperwork.

Across all five commodities, the dominant means of deception will be digitally enabled documentation fraud.

List 3: the ‘emerging watchlist’

The previous two high-risk lists are based on documented and historic patterns, enforcement cases and/or new legislative pressures. This list, however, is more speculative, considering foods and ingredients impacted by multiple pressures building up so quickly that checks, controls and regulations are struggling to keep pace. Plant-based protein isolates (pea, fava, lentil) are included owing to rapidly growing demand, sustainability positioning and global sourcing creating many opportunities for dilution and substitution. Alternative oils such as algae and camelina have been selected due to climate pressure on conventional vegetable oils and competition from biofuels. I believe the likelihood of undeclared blending of these oils is high.

More obviously, speciality rice varieties such as Basmati and Thai Jasmine appear on the list because climate shocks and export controls are destabilising supply, increasing the likelihood of variety and origin substitution. Climate-positive and low-carbon foods are in this list as they are likely to demand premiums based on consumer demands. This, combined with what I can see are very immature verification frameworks for auditing such products, makes greenwashing and certificate fraud particularly attractive.

My other selections reflect upstream invisibility and weak or no consumer-facing scrutiny. Aquaculture feed ingredients are included because fishmeal shortages and sustainability regulations create incentives for protein substitution and the use of undeclared inputs, especially antibiotics. Downstream such fraud is very difficult to detect without robust testing and auditing schemes in place. Processed fruit and vegetable ingredients (purees, concentrates) are exposed as climate-driven crop failures increase dilution and sugar addition risks. It may surprise some, but I also include food-grade minerals and salts in this list as the geopolitical concentration of mineral resources increases the risk of industrial-grade substitution. Finally, I’ve included digital-only food brands – not because of specific ingredients, but because e-commerce models often have very weak audit trails, allowing the complete fabrication of provenance narratives.

List 4: ‘artificial intelligence’

Taken together, these developments indicate that food fraud in 2026 and beyond will increasingly be invisible, document-centric and digitally sophisticated.”

While AI will surely help strengthen food fraud detection in the coming years, I firmly believe it will also materially increase the capability, scale and sophistication of food fraud itself.

During 2026 and onwards, AI will act as a force multiplier for fraudsters by lowering barriers to entry, accelerating deception and exploiting the growing dependence of regulators and industry on digital evidence rather than physical verification and laboratory testing.

One of the most immediate risks is AI-generated documentation and traceability fraud. Large language models and generative AI systems can already produce highly convincing certificates of analysis, organic certificates, sustainability declarations and regulatory correspondence tailored to specific jurisdictions. I have already seen examples of these. Fraudsters will be able to generate convincing but fake compliance histories, complete with plausible audit trails, geolocation metadata and the required levels of consistency across documents. This is particularly dangerous in regulatory frameworks such as deforestation-free supply chains, organic certification and low-carbon labelling, where enforcement increasingly relies on documentation (thus impacting List 2).

A second emerging threat is false provenance claims and origin laundering at scale. AI systems can blend satellite imagery, historical land-use data, weather records and logistics timelines into coherent but false narratives of origin. Fraudsters may generate falsified farm boundaries, deforestation-free histories, or climate-positive production claims that pass existing checks. When combined with shell companies, ghost farms or fake exporter identities, this form of fraud becomes exceptionally difficult to detect.

AI will also enable adaptive fraud that learns faster than regulatory controls. Machine-learning systems can be trained to observe inspection patterns, sampling triggers and enforcement thresholds, allowing fraudsters to tune adulteration levels or documentation irregularities to sit just below detection limits. This creates a dynamic adversarial environment in which fraud strategies evolve continuously in response to regulatory behaviours.

A fourth risk lies in AI-enabled supply-chain impersonation and digital infiltration. Voice cloning, automated negotiation bots and deepfake video calls can be used to impersonate legitimate suppliers, laboratories, certification bodies or regulators. In highly digitalised procurement and remote-audit environments, this blurs the boundary between cybercrime and food crime, enabling fraudsters to redirect payments, validate non-compliant goods or bypass controls.

Finally, I believe AI may facilitate fraud in novel and emerging ingredients where analytical testing is weak. For fermentation-derived ingredients, alternative proteins and functional compounds, AI can be used to engineer products that appear compliant while being diluted or substituted. Combined with the regulatory unfamiliarity I have referred to, this creates conditions for long-term, low-visibility fraud.

Taken together, these developments indicate that food fraud in 2026 and beyond will increasingly be invisible, document-centric and digitally sophisticated. The strategic challenge is that AI will make fraud harder to detect and faster to scale. Future food integrity systems must therefore treat AI not only as a defensive tool, but as a credible adversarial capability, requiring counter-AI strategies, data-integrity audits, behavioural analytics and renewed emphasis on physical verification and fingerprint-based testing.

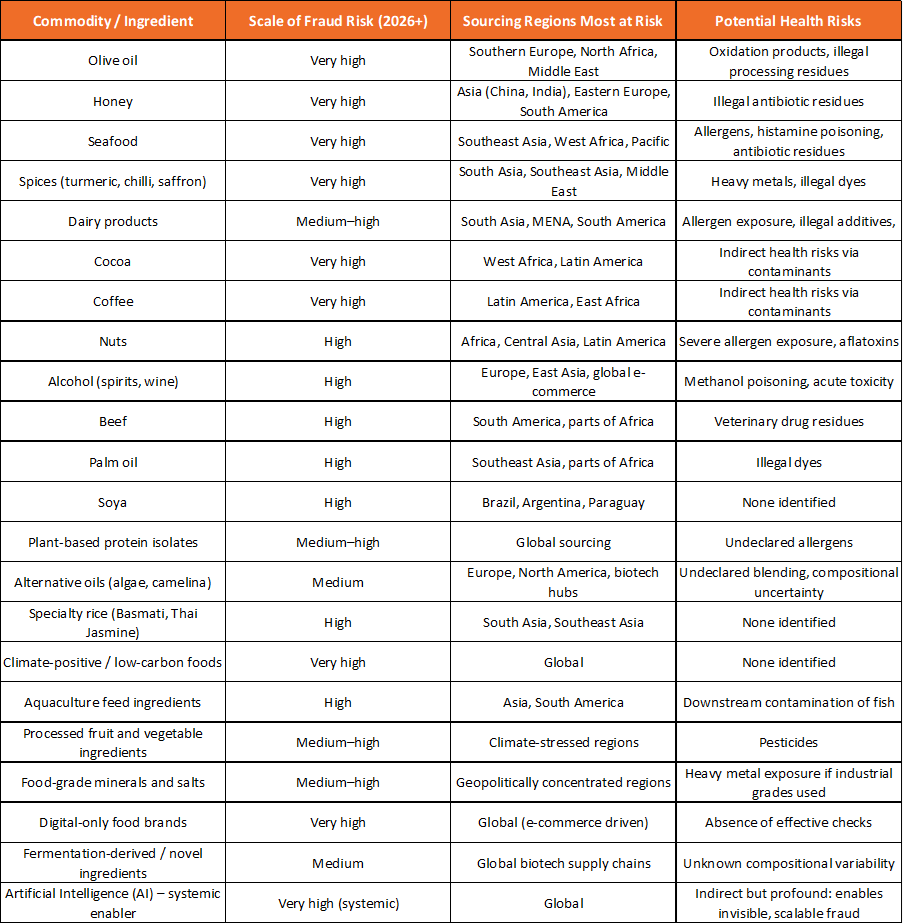

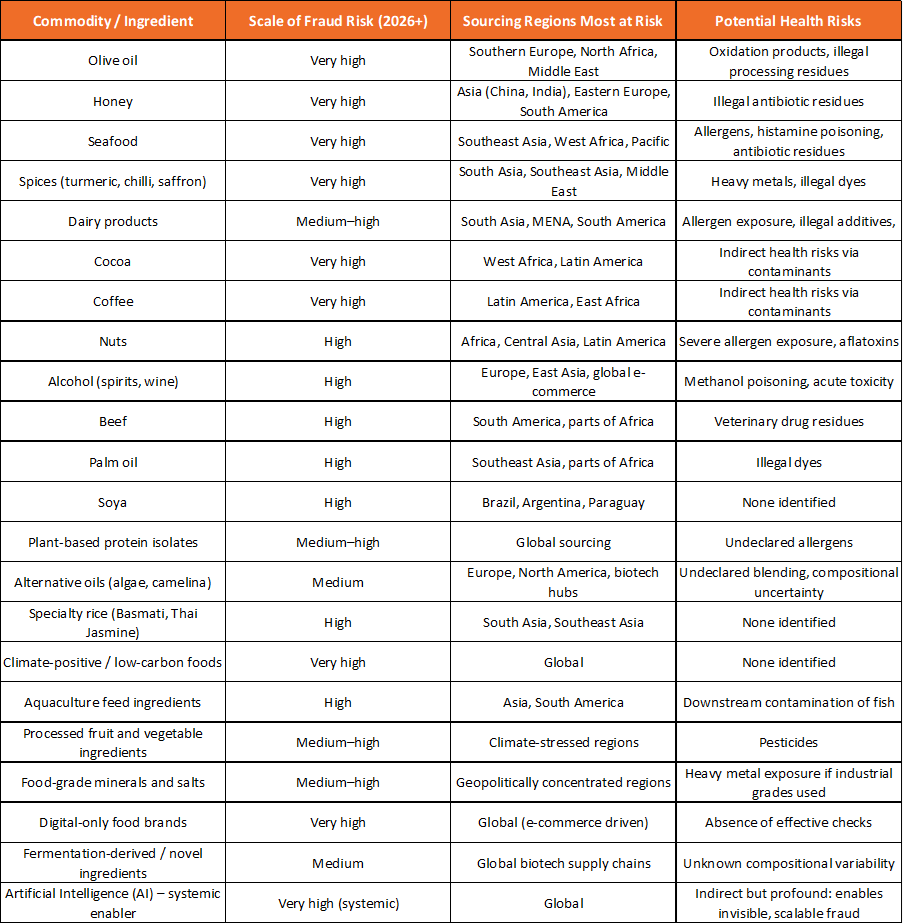

With reference to these four lists, with some commodities appearing in several, I have included a summary of all the commodities and ingredients cited, the main sourcing locations and the potential impacts on human health associated with the various types of fraud I believe will occur. This article is not intended to be alarmist, but rather to establish a forward-looking assessment of food fraud risk in 2026 and beyond, built around four complementary risk lists that have drawn on a wide range of intelligence sources. Together, the lists serve to illustrate how fraud is no longer confined to a small group of familiar commodities, but is expanding upstream into ingredients, sustainability claims and digital provenance, driven by climate disruption, geopolitical instability, regulatory pressure such as EUDR, and accelerating digital trade.

As the watchlist of vulnerable commodities and ingredients grows, I firmly believe that upstream testing using mobile advanced fingerprinting technologies will become essential to verify authenticity before products enter complex global supply chains. At the same time, data science and AI will play an enormous dual role: exploited by fraudsters to generate convincing but false narratives, yet also indispensable for regulators and industry to detect anomalies, integrate intelligence and move towards predictive, risk-based control systems. The central message is that food fraud in the next decade will be increasingly data-driven, less visible and faster to scale, requiring a fundamental shift in how food integrity is protected if trust in the global food system is to be maintained.

A consolidated risk table covering all commodities and ingredients referenced across the four lists. It has been structured to support industry and regulatory horizon scanning and strategic prioritisation. It integrates the scale of the fraud risk, geographic sourcing risks and potential health implications.

Related topics

Food Fraud, Food Safety, Ingredients, Quality analysis & quality control (QA/QC), Regulation & Legislation, retail, Sanitation, Shelf life, Supply chain, The consumer, Traceability, Trade & Economy, World Food