Inspired by A Christmas Carol, this fictional narrative follows a global food executive forced to confront the human cost of his decisions. Drawing on real world failures and insights from Dr Darin Detwiler and international food safety leaders, the story explores how culture, leadership and risk shape outcomes across the food system.

This holiday story (inspired by Charles Dickens’ 1843 novella A Christmas Carol) is a cautionary tale for the food industry. It follows CD Screege, a high-ranking executive at a global food manufacturer who sees food safety as a box to check – not a moral responsibility. During a long series of business trips, however, Screege is confronted by the true cost of that thinking – not just in money, but in lives.

Though fictional, this story reflects real and ongoing struggles between profit and public health. In an industry that feeds billions, the margin for error, where food safety is concerned, is small and the consequences of neglect are often invisible until it’s too late.

Chapter one: the ghost of food safety past

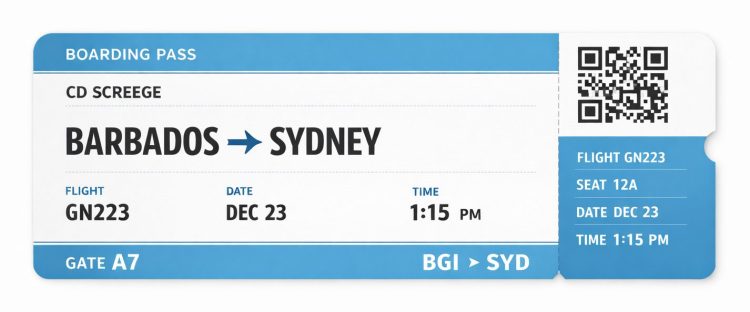

Flight: Los Angeles to Barbados

CD Screege, Vice President of a multinational food manufacturer, stood in the private lounge of LAX with his usual blend of confidence and calculation. His goal for this trip was simple: secure year-end profit targets. His method: enforce mandatory holiday production shifts at the company’s key locations in Los Angeles, Barbados, Sydney and Dubai.

His phone buzzed; it was his assistant (and brother-in-law) Robert calling from the corporate office.

“Hey, CD, your sister wanted me to ask if I could take a few days off next week. Sarah’s due to give birth soon and as it’s our first child she’s hoping I’ll be there when the baby arrives.”

Screege barely paused. “No time for that,” he said. “We’re under pressure to close the year strong. Everyone’s working through the holidays. No vacations. No exceptions. I’m flying out to tell the teams myself.”

“Sarah’s going to be very disappointed, but I get it, I guess. Also … did you get the report I forwarded from the director of food safety?” Robert asked. “We may need to hold off on the next shipment until test results come back.”

Screege rifled off a reply: “I’m sure it’s fine – Just ship it!”

“Are you sure?” asked Robert, sheepishly.

There was intentional silence on the other end of the line.

“…Okay,” Robert said quietly. “Safe travels.”

Screege hung up, unmoved. His mind was already on Barbados. On deadlines. On the big bonus he will get at the end of the year when he hits his targets. He boarded the plane with his coat in one hand and a magazine in the other.

Settling into first class, Screege glanced at the passenger taking the seat beside him.

Screege said: “I think I recognise you from a conference.”

Dr Darin Detwiler introduced himself: “Hello, yes… I’m a food safety advocate and author. You might have seen me in the Netflix documentary ‘Poisoned’.”

“I never watched that one…bunch of crying parents…” Screege remarked bluntly.

“Oh, yes, they used to call me that too…” muttered Detwiler under his breath.

Screege introduced himself as the VP of a major food company. He spoke proudly, somewhat unsolicited, about his company’s global scale; sidestepped details about recent shortcuts on validation testing, and dropped a line about “pushing production hard this quarter.”

Detwiler offered only a nod.

Soon after takeoff, Screege reclined his seat and drifted off to sleep.

He woke later to find the plane was empty. No passengers, no crew; just the faint hum of machinery.

He stepped off the plane and walked directly into the waiting room of a hospital. The sign above the reception desk read ‘Seattle Children’s Hospital.’ The calendar on the wall read ‘February 1993.’

Mariah Carey’s ‘Hero’ could be heard playing faintly while television monitors flashed headlines about a deadly E. coli outbreak tied to a fast-food chain.

Screege turned to leave, but the plane door was gone. To his surprise, Dr Detwiler appeared beside him, ushering him into an intensive care room, where a young Darin sat on the edge of a hospital bed, holding a toddler, pale and lethargic. The child pointed to his IV bag and called it his ‘bottle.’

Indicating his younger self and his son, Dr Detwiler tells Screege, “That’s my son Riley; he was 16 months old.”

“Why is he here?” asked Screege.

“Doctors just confirmed that Riley is sick with E. coli and has developed haemolytic uraemic syndrome (HUS)” Detwiler explained. “He didn’t eat the contaminated burger; he became ill from another child in his daycare centre who did eat the contaminated food. The doctors are explaining to families about person-to-person infections.”

Screege offers an empty, yet authoritative, assurance: “Tough break. I’m sure they’ll figure it out.”

Screege was then transported into a different room where Riley lay motionless in the paediatric ICU. His small frame was nearly lost beneath a tangle of tubing and the towering machinery encircling his bed. Monitors beeped in quiet succession, each tone a sterile reminder of that microbial menace that had taken over where childhood once lived. The soft hiss of the ventilator filled the space between breaths he could no longer take on his own.

His parents stood in a corner of the room, speaking in low tones with the attending physician. Their voices were tight with fear while feigning hope. Riley remained caught in the machinery of modern medicine, suspended between the promise of intervention and the silence of outcome. After a moment of taking in the whole scene, Dr Detwiler reappears beside him.

Screege looked on without emotion. “Sad,” he said. “But accidents happen. What’s the worst that could come of it?”

Moments later, they are standing outside. The townspeople stood in small clusters, coats drawn tight against the cold, their eyes fixed on the family at the front. A few news crews lingered at a respectful distance. No one spoke above a whisper.

The reverend’s voice rose over the frostbitten stillness, offering words meant to comfort, though none could. The ground beneath him was hard, crusted with ice. The coffin, stark white and heartbreakingly small, was slowly lowered into the frozen earth.

Off to the side, a Navy colour guard stood at attention. Their faces were unreadable, their breath fogging in the cold air. They had not come for ceremony; they had come for a sailor’s son and to honour one of their own.

Young Darin stepped forwards. His posture had the unmistakable bearing of a submariner, but his face told a different story. It was the face of a father missing a part of himself. No uniform prepares you for that kind of pain.

Reaching into his jacket Darin took out his silver dolphins – the insignia of the submarine service, earned through grit, precision and pressure deeper than most will ever know. He placed them gently atop the coffin – a gesture that held a lifetime of meaning.

That word ‘Isolated’ has cost countless lives.”

Stepping back, Darin raised his hand in a final salute and stood in silence. Not as a veteran and not yet as an advocate…but as a father, saying goodbye.

Screege shifted. “That was long ago,” he said. “That was an isolated case. Those running that show were careless criminals and should have gone to jail.”

Dr Detwiler’s tone sharpened. “That word ‘Isolated’ has cost countless lives. It’s what people like you say when they want to avoid responsibility.”

Screege was quick to offer a rebuttal: “My company is too big to fail like that.”

Dr Detwiler fixed his gaze on Screege, his voice low but commanding: “This isn’t over. Before your trip is complete, two more voices will visit you. Listen to them. Your future depends on it.”

Screege wakes abruptly to a flight attendant gently shaking him. He is the very last to exit the plane in Barbados.

At his company’s island facility, he meets with the local leaders in a boardroom to deliver a canned, predictable motivation statement, before leading into a rant about the need to increase productivity to achieve profit goals. All thoughts of the dream had faded.

“Let’s remember, team: success doesn’t come wrapped in tinsel. It comes from pushing harder, cutting slack and keeping our eyes where they belong – on the margins, not the mistletoe.” Screege preached with the practiced rhythm of someone who has given up listening.

He proceeded to dictate that the local employees will not get any time off for the holidays.

Chapter two: the ghost of food safety present

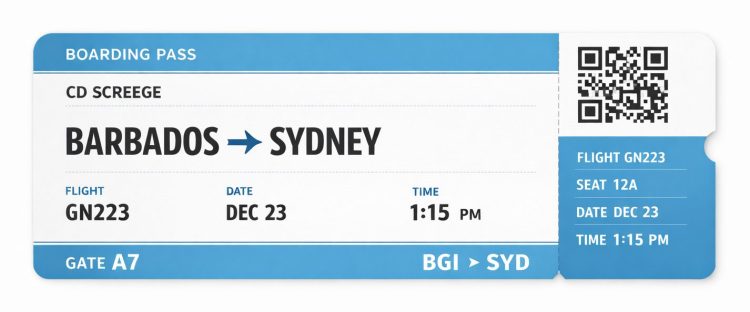

Flight: Barbados to Sydney

Leaving Barbados for Sydney, Screege found himself sitting beside Dr Carol Hull-Jackson, an internationally respected veterinary public health expert and food safety advocate for developing nations, who worked between Barbados and Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia.

She was reviewing laboratory reports, food recalls and testing results.

They exchanged names. Downplaying his title, Screege mentioned he was “in operations” and avoided talking about the working-through-the-holidays enforcement tour.

Once again, sleep overtook him after the flight took off.

Screege awoke suddenly, in a high-tech public health laboratory buzzing with activity and was surprised to find Dr Hull-Jackson standing beside him. She guided him past busy researchers, technologists, machines humming as data are processed, and screens covered in trends, timelines and outbreak tracking. Clearly, a lot was happening behind the scenes.

“These are this month’s regional cases,” she said, pulling up test results. “Here’s one tied to Salmonella. And this one, associated with undeclared allergens, triggered adverse reactions and a major food recall.”

She tapped her screen and pulled up a report. Screege’s company’s name appeared in the file.

“Mr Screege, these batches, produced by your company in Barbados during the holiday ramp-up, were contaminated with Salmonella” she admonished.

Screege shrugged. “Still, nothing serious happened; no one died!”

Leadership doesn’t mean waiting until someone gets hurt, or for a costly food recall to occur. It means acting when you see risks and controlling them.”

Guiding him into another room, Screege noted screens lab screens flicking through incident reports from around the world: mislabelled allergens from products in New Delhi, expired meat with fraudulent package labels in São Paulo, aflatoxin spikes associated with maize flour in Nairobi… Different products, various locations, same pattern: shortcuts, silence, suffering. Analysts were cross-referencing global reports with regional alerts, consumer complaints and hospital reports.

“Leadership doesn’t mean waiting until someone gets hurt, or for a costly food recall to occur” asserted Dr Hull-Jackson. “It means acting when you see risks and controlling them. Your decisions have consequences that impact lives, even if you’re not willing to admit it.”

Screege crossed his arms. “Scientists always overreact. We follow business basics.”

Dr Hull-Jackson’s expression darkened. “No. YOU follow what’s convenient. And that is precisely why this lab remains overwhelmed. Nothing will change until leadership mindsets about food safety change. And the grim truth is, they haven’t in three decades.”

Screege quipped: “We all could use some miracles!”

“We don’t need miracles, Mr Screege,” she countered. “We need food safety leadership and accountability. And that starts at the top with decision makers like you, because food safety is everyone’s business!”

“You’ll be visited by one more voice,” she said quietly, her tone sombre. Then, as she turned, walking away without looking back, her warning echoed down the laboratory hallway: “Pay attention! It’s not too late – yet.”

Screege was again woken by a flight attendant as he landed in Sydney.

The last time Screege had been in Australia, the mood had been far more volatile. It was early 2018, during the rockmelon (cantaloupe) listeriosis outbreak that had gripped New South Wales. Twenty-five people became seriously ill. Seven died. One woman miscarried. The pathogen didn’t respect borders – contaminating export shipments, it sickened consumers in Singapore before anyone connected the dots.

Screege hadn’t stayed long back then; just enough to issue a tightly controlled press release and to calm investors. He assured them, without a shred of validation, that the contamination had not originated in their facility.

Technically, that was true. The bacterium hadn’t entered there. It had only passed through.

Now, seated once again in the boardroom of his company’s Sydney operation, Screege scanned the familiar faces across the table. The holiday lights blinking on the far wall seemed far out of place.

He stood and repeated the same line he’d delivered in London, as though reading from a script.

“Let’s remember, team: success doesn’t come wrapped in tinsel. It comes from pushing harder, cutting slack and keeping our eyes where they belong: on the margins, not the mistletoe.”

The room fell quiet. Screege’s words landed, but not as firmly. Something had shifted. His all-too common cadence cracked at the edges. The ghosts hadn’t vanished … they lingered in the silence between sentences.

Though no one spoke about it, everyone remembered 2018.

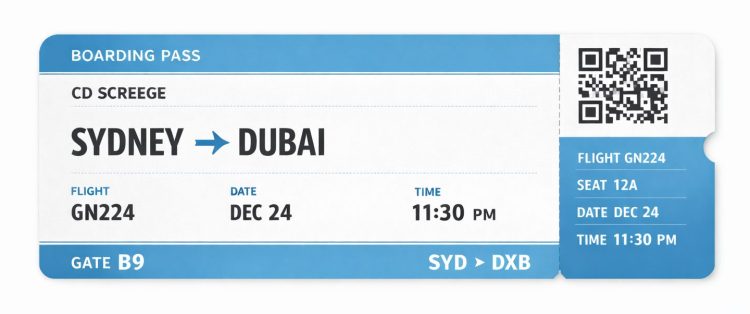

Chapter three: the ghost of food safety yet to come

Flight: Sydney to Dubai

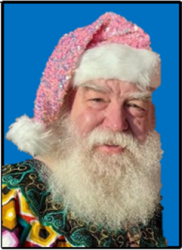

After a whirlwind visit to his Sydney operations, Screege boarded a direct flight to Dubai. He found himself next to a bearded, kind-eyed man in a Hawaiian shirt and chef pants, with a voice that was both calm and commanding. He introduced himself as Dr Julian Cox, an Australian academic and a globally respected authority on food safety.

With the long haul ahead, the last thing Screege wanted was to dive into a food safety conversation. He barely managed a greeting before slipping into a deep sleep.

He woke up standing next to Dr Cox, now in Christmas-themed attire, reminiscent of Santa Claus. Without a word, Dr Cox escorted him into the middle of a press conference. Several executives from Screege’s company were on screen, delivering a carefully worded apology. They acknowledged media reports about a nationwide outbreak tied to one of their supposedly shelf-stable products. Reporters questioned them about the many seriously ill in hospitals across the country, noting that some families had already filed lawsuits.

Screege stood silently in the back of the room, unable to speak. He heard “botulism”, knowing it to be a rare, but potentially fatal, intoxication. He remained silent.

Dr Cox then took him to a hospital ward, where a child in the far corner bed lay in a critical condition.

“Why are you showing me this? Another hospital ward? Humph!” complained Screege. Dr Cox indicated the hospital bed, where he finally recognised his sister and brother-in-law at the bedside of who could only be their daughter. His sister Sarah held the child’s hand, whispering her name.

Screege staggered back.

“That’s my… niece?” he queried, stunned. “But… she hasn’t even been born yet.”

“She was, and she’s been healthy, up until now,” Dr Cox said. “Then she ate one of your company’s products during a holiday meal. The validations were skipped. The sanitation programme was rushed. You made the call. And now she’s here.” Screege was speechless.

“I didn’t know,” he finally said. “I didn’t think…”

Dr Cox turned to him and in his calm yet commanding voice, he stated firmly, “You didn’t want to think. You had the data. You ignored them. You had the warnings. You brushed them aside.”

Silence filled the room, except for the beep of the bedside monitor, the daughter’s shallow breathing and her mother’s sobs.

CD Screege awoke as the plane touched down in Dubai. For a long moment, he sat frozen in his seat. The flight attendants moved through the cabin. The lights were on.

Passengers around him stretched and prepared to disembark.

But something in him had changed.

Turning to Dr Cox, he shook his hand and murmured “Thank you, that meant more than you can imagine.”

Dr Cox looked confused, but offered Screege a “you’re welcome,” in response. Screege then reached for his phone and dialled Robert.

“You need to connect me to operations,” he told Robert. In a measured tone, he spoke. “Effective immediately, halt all distribution. I want full validation reports on every product line. And I want a sanitation audit before anything else ships.”

A pause. Incredulous, Robert asks “Are you sure sir?”

“Yes,” Screege replied. “I’ve never been more serious. No product ships until we’ve verified everything. And tell everyone to go home for the holidays. We’re not gambling with people’s lives anymore.”

Robert responded excitedly: “You got it! Verify everything, and then we’re on holidays!”

Screege added: “By the way, how is my sister, the ‘mom-to-be’ doing?”

“She’s doing very well, CD!” Robert replied. “And we’d like it very much if you’d join us for Christmas dinner.”

“Hey, Robert…” Screege implored. “Call me Charlie. And yes… Christmas dinner sounds wonderful. What foods can I bring?”

At his company’s Dubai facility, he met with the local leaders in a boardroom to listen to their reports about how Dubai is a key export hub and leader in food innovation. He learned of their progress and addressed several of their specific concerns, including how international compliance and Halal standards intersect with global safety expectations.

Success doesn’t come from cutting corners or chasing margins. It comes from protecting people – protecting every plate, every product, every time.”

“Let’s be clear,” Screege began, no longer standing at the head of the table, but seated among his team. “Success doesn’t come from cutting corners or chasing margins. It comes from protecting people – protecting every plate, every product, every time.”

He paused, to let the words land fully. This time, he meant them, and his team knew it.

“I used to think holidays were distractions. Now I see they are reminders … that what we do matters most when no one’s watching. Food safety is not ticked boxes. It is people … those who make food and those who consume it. In fact, food safety is a promise from one to the other. And going forwards…we keep it, not because it’s easy or efficient, but because it’s right.”

Gone was the rehearsed cadence. Screege spoke slowly, listening between his own sentences, inviting discussion and finally offering true leadership.

“We lead with care now. That’s not weakness. That’s our standard.”

Epilogue By Dr Darin Detwiler

Stories like this are fiction, but the choices within them are not. For more than thirty years, I’ve sat with families who lost someone they loved to a preventable failure in our food system. Their question is always the same: How could this have happened? And the answer is almost never a single mistake. It’s a pattern. A warning set aside. A shortcut justified. A moment when pressure outweighed principle.

Screege’s journey is a reminder that these patterns are not inevitable. They are built by people, shaped by culture and changed the same way. He didn’t set out to cause harm. Few leaders do. But he worked within a system that rewarded speed, softened dissent and treated safety as a cost, not a cost of doing business. It took a dream of a dark future – and a hard look at his own decisions – to understand the cost of that mindset and to choose differently.

The risks in this story are real. The consequences are real. But so is the opportunity.

Leadership is not something we wear in our title. It’s something we reveal in quiet moments, when the pressure rises and no one is watching. If you’re in a position to make those choices, I hope this story travels with you into the season ahead.

By the way, in the end, Screege didn’t save the world. He simply made one better decision. One that might protect a child, a family, a future. And that’s how real change begins. Not with grand gestures or headlines, but with a shift in how we see our work and the trust placed in us. With the courage to say, even once, ‘not this time.’

And sometimes, that’s enough to change everything.

Meet the authors

Dr Darin Detwiler (USA), is New Food’s Distinguished Global Fellow and a recognised authority in food policy, public health and food safety innovation. With a career spanning government advisory roles, academic leadership and industry engagement, he has influenced national food regulations, corporate strategies and education across the US and internationally.

He is the author of Food Safety: Past, Present, and Predictions and Building the Future of Food Safety Technology and he appears in the Netflix documentary Poisoned. As founder of PEP Nexus and co-host of the podcast Confessions of a Food Safety A**hole, Dr Detwiler brings a bold, solutions-focused voice to the evolving dialogue around accountability and culture in the global food system.

Gennette Zimmer, MBA, MSc (USA), CEO of PEP Nexus, is a data analyst and Producer / Editor / Co-Host of “Confessions of a Food Safety A**hole” (Podcast), where she blends candid commentary with expert insights to challenge the status quo in food safety culture.

Her work bridges science, strategy and storytelling to drive meaningful change in the global food industry. PEP Nexus is a collaborative media platform that focuses on ‘protecting every plate’ (hence the acronym) within the global food system.

Dr Carol Hull-Jackson (Barbados / Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia) is a veterinary public health consultant with extensive expertise in food safety, quality assurance, microbiology and zoonotic diseases. She serves as Chairperson of the Food Science Council for Export Barbados, where she plays a key role in advancing the nation’s food industry through science-based policy and innovation.

Dividing her time between Barbados and Kuala Lumpur, Dr Hull- Jackson brings a global perspective to her work, promoting international best practices in food systems and public health. Her career reflects a commitment to strengthening food safety capacity and safeguarding public health across borders.

Dr Julian Cox (Australia) is Associate Dean (International) at UNSW Sydney’s Faculty of Engineering and a renowned expert in food microbiology and food safety. With a career spanning academia, industry collaboration and regulatory consultation, he has contributed extensively to research and education in foodborne pathogens and risk management.

Widely recognised for his engaging public outreach (especially under the persona of ‘Food Safety Santa’), Dr Cox promotes food safety awareness with a unique blend of science and seasonal humour. His leadership reflects a commitment to both global academic engagement and practical solutions to public health challenges.

BONUS MATERIAL

Here are five reflections, drawn directly from Screege’s journey, for leaders who want to build stronger, safer organisations, where responsibility doesn’t depend on a ghostly wake-up call.

- What behaviours do your systems unwittingly encourage when no one’s looking?

Screege dismissed the safety director’s warning with, “I’m sure it’s fine…just ship it.” He wasn’t trying to be reckless: he was responding exactly as his incentive structure taught him to. If your systems reward speed and production, that is what people will prioritise, especially under pressure.

Ask yourself whether people in your organisation make decisions because they believe it’s right, or because they believe it’s expected.

- Does your organisation chart concentrate control or distribute responsibility?

The safety team had concerns, but none of them had the authority to pause a shipment. Decisions should be made where the information lives. Screege’s team had the data, but not the influence.

Ask yourself: Who is allowed to say ‘stop’ in your company? And do they believe they’ll be supported when they do?

- Are weak signals being surfaced, or filtered out?

In the Sydney lab, Screege saw analysts overwhelmed by minor alerts that had never been escalated. Most major failures begin as small anomalies – a mislabelled allergen, a testing delay, a gut feeling. But if people are trained to minimise, delay, or defer, those signals never result in action.

Ask yourself: What are you doing to make warning signs visible and safe to raise?

- Do people have the clarity (and confidence) to act?

Dr Hull-Jackson didn’t ask Screege for permission. She showed him the consequences and told the truth. Great organisations don’t rely on compliance. They build clarity around purpose and trust people to act on it.

Ask yourself: If someone saw a risk in your company today, would they feel permitted to speak up … or expected to?

- What legacy do your decisions leave – and who pays for them?

By the time Screege saw his future niece in the hospital, it was too late. The risk he had ignored had made its way home. In leadership, you often don’t personally experience the consequences – but someone else does. The most vulnerable people in the system are more likely the ones furthest from the decision-making.

Ask yourself: Are you close enough to the outcomes your choices create or are you insulated by layers of structure?

You don’t need to wait for three ghosts to course-correct. Leadership is not about seeing around corners. It is, however, about designing systems that don’t require heroics to do the right thing.

In food safety, lives are at stake. And that means leadership isn’t a role, it’s a responsibility – shared at every level, built into every decision.

Make the system better and the people will rise to meet it.

Food safety is not a seasonal message. It is a daily promise made to every parent, child, caregiver and consumer who trusts the industry to get it right. That trust is not built through speeches or slogans. It is built through decisions that honour the people we may never meet but always serve.

This year, I hope leaders choose to act before the ‘ghosts’ appear. A single thoughtful decision can protect a child, a family and a future.

Sometimes, that is enough to change everything.

Related topics

Allergens, Contaminants, Data & Automation, Food Fraud, Food Safety, Health & Nutrition, Hygiene, Ingredients, Labelling, Outbreaks & product recalls, Packaging & Labelling, Pathogens, Processing, Quality analysis & quality control (QA/QC), recalls, Recruitment & workforce, Regulation & Legislation, retail, Sanitation, Shelf life, Supply chain, The consumer, World Food