New study finds iron-fortified hemp biochar sharply reduces PFAS forever chemicals entering radishes from contaminated soil, offering food producers a promising mitigation tool.

Iron-fortified hemp-derived biochar reduces per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances bioaccumulation in radish (Raphanus sativus L.)

Credit:

Trung Huu Bui, Mandeep Kaur, Nubia Zuverza-Mena, Sara L. Nason, Christian O. Dimkpa, Jasmine P. Jones & Jason C. White

Iron-fortified hemp biochar can significantly cut the amount of PFAS “forever chemicals” moving from polluted soils into food crops, according to new research showing marked reductions in contamination of greenhouse-grown radishes.

Per and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) are extremely persistent industrial chemicals that can move through soil, water and air and build up in crops and people.

The study, carried out using PFAS-contaminated sandy loam soil from a former firefighting training area in Connecticut, examined whether biochar made from agricultural hemp waste could lock PFAS in place and restrict their transfer into edible plant tissues.

Fortified biochar delivers significantly lower PFAS uptake

Researchers found that iron-fortified hemp biochar reduced total PFAS levels in whole radish plants by around 37 percent compared with unamended soil. The fortified biochar also outperformed non-fortified biochar, lowering total plant uptake by nearly 46 percent.

Lead author Trung Huu Bui said:

PFAS do not simply disappear once they reach farmland, and our results show that they can move efficiently from soil into the foods we grow. Iron fortified hemp biochar offers a promising way to trap these contaminants in the soil and reduce their entry into the food chain without sacrificing plant growth.”

The test soil contained roughly 576 nanograms of total PFAS per gram, dominated by PFOS, which made up about 60 percent of the contamination burden. Biochar was produced from hemp stems and leaves at temperatures between 500°C and 800°C, with some batches soaked in an iron sulphate solution before pyrolysis to add iron-rich sorption sites.

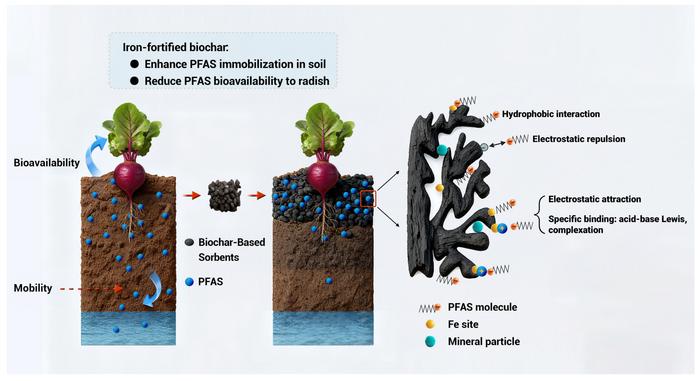

How iron fortification improves PFAS retention

Laboratory analyses showed that biochar created at 500°C delivered the highest surface area and the greatest concentration of oxygen-containing functional groups, properties that improved PFAS retention compared with material made at higher temperatures. Iron fortification further increased porosity and introduced iron oxide and hydroxide sites capable of attracting negatively charged PFAS molecules.

To test performance in crops, researchers mixed selected biochars into the contaminated soil at 2 or 5 percent by weight and incubated the soils for 90 days. Radish seedlings were then grown for four weeks before PFAS were measured in soil leachates, shoots and edible bulbs using high sensitivity liquid chromatography mass spectrometry.

Across all treatments, radishes grown in unamended soil accumulated high levels of short-chain PFAS, with bioaccumulation factors above 1, particularly for short-chain carboxylic and sulfonic acids. When iron-fortified hemp biochar produced at 500°C was added, PFAS in edible bulbs dropped by around 25.7 percent compared with unamended soil, with especially strong reductions seen for several short-chain compounds of concern.

The researchers concluded that iron-fortified hemp biochar works by combining physical and chemical mechanisms. Enhanced pore structure increases the material’s capacity to hold contaminants, while newly created positively charged and hydrophilic sites support electrostatic attraction, ligand exchange, hydrogen bonding and complex formation with PFAS head groups. This limits the freely dissolved fraction available for plant uptake and slows the migration of PFAS through soil pore spaces.

Implications for food safety and next steps

The findings underline the food-safety risks facing producers operating on PFAS-impacted land, as even root vegetables grown below the soil surface can accumulate substantial quantities of short-chain PFAS. For growers seeking practical mitigation measures, the study points to low-dose iron-enriched biochar as a viable tool for reducing dietary exposure while improving soil properties.

The researchers now recommend field-scale trials to examine long-term performance, interactions with soil microbes and whether similar mitigation effects can be achieved across a wider range of crops and PFAS mixtures.

Food and beverage professionals seeking deeper insight into PFAS risks and regulatory developments can learn more in New Food’s upcoming webinar, PFAS in Food: Regulations, Analytical Challenges and Case Studies, taking place on 10 December.